Microsoft has reached a historic milestone in its development in the Artificial Intelligence (AI) space.

A team of Microsoft researchers believe they have created the first machine translation system that can translate sentences of news articles from Chinese to English with the same quality and accuracy as a person.

The researchers claim to have achieved a “human parity” on a commonly used test set of news stories that were moderated by external bilingual human evaluators who compared Microsoft's results to two independently produced human reference translations.

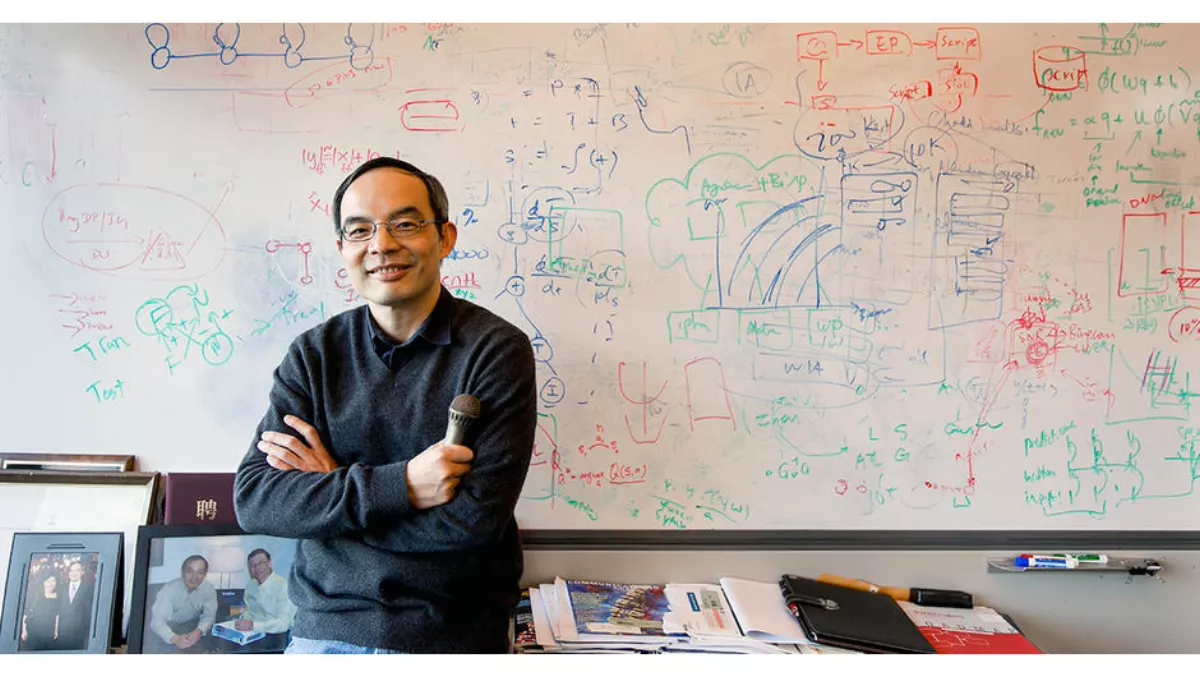

The technical fellow in charge of Microsoft's speech, natural language, and machine translation efforts, Xuedong Huang calls it a major milestone in one of the most challenging natural language processing tasks.

“Hitting human parity in a machine translation task is a dream that all of us have had,” Huang says. “We just didn't realise we'd be able to hit it so soon.

“The pursuit of removing language barriers to help people communicate better is fantastic,” he adds. “It's very, very rewarding.

Xuedong Huang, technical fellow in charge of Microsoft's speech, natural languageand machine translation efforts

Despite the excitement surrounding this breakthrough in AI in language translation, Microsoft researchers warn that this it doesn't mean all problems in machine learning translation are solved.

The assistant managing director of Microsoft Research Asia and head of a natural language processing group that worked on the project, Ming Zhou, says that although the team is thrilled to achieve the human parity milestone, there are still many challenges ahead, like test the system on real-time news stories.

Partner research manager of Microsoft's machine translation team Arul Menezes says the team set out to prove that its systems could perform as well as a person when it used a language pair on a test set that includes the more commonplace vocabulary of general interest news stories.

Arul Menezes, partner research manager of Microsoft's machine translation team

Arul Menezes, partner research manager of Microsoft's machine translation team

“Given the best-case situation as far as data and availability of resources goes, we wanted to find out if we could actually match the performance of a professional human translator,” says Menezes.

Menezes says the research team can apply the technical breakthroughs they made here to Microsoft's commercial translation products.

Menezes says that this will pave the way for more accurate and natural-sounding translations across other languages and for texts with more complex or niche vocabulary.

Three research teams were behind the human parity milestone. The teams were based in Microsoft's Beijing, Redmond and Washington labs, and worked together to add a number of other training methods that would make the system more fluent and accurate.

Principal research manager with Microsoft Research Asia in Beijing Tie-Yan Liu led a machine learning team that worked on the project. Liu says, “Much of our research is really inspired by how we humans do things.

Techniques and methodsDual Learning

One method the researchers used is dual learning, a method Microsoft describes “fact-checking the system's work”: Every time the researchers sent a sentence through the system to be translated from Chinese to English, the research team also translated it back from English to Chinese.

Microsoft says this method is similar to what people might do to make sure that their automated translations were accurate, and it allowed the system to refine and learn from its own mistakes.

Developed by the Microsoft research team, dual learning can be used to improve results in other AI tasks, the company claims.

Deliberation Networks

Another method used in the project is Deliberation Networks, which Microsoft says is similar to how people revise their own writing by going through it over and over again.

The researchers taught the system to repeat the process of translating the same sentence over and over, gradually refining and improving the response.

Joint Training

Joint Training is a technique used in the research to iteratively boost the English-to-Chinese and Chinese-to-English translation systems.

With Joint Training, the English-to-Chinese translation system translates new English sentences into Chinese in order to obtain new sentence pairs.

These pairs are then used to augment the training dataset that is going in the opposite direction, from Chinese to English. The same procedure is then applied in the other direction. As they converge, the performance of both systems improves.

Zhou says he expects these methods and techniques to be useful for improving machine translation in other languages and situations as well. He said they also could be used to make other AI breakthroughs beyond translation.

“This is an area where machine translation research can apply to the whole field of AI research,” he adds.

No right answerThe test set the researchers used contains around 2000 sentences from a sample of online newspapers that had already been professionally translated.

Microsoft ran multiple evaluation rounds on the test set, randomly selecting hundreds of translations for evaluation each time.

To verify that Microsoft's machine translation was as good as a person's translation, the company hired a group of outside bilingual language consultants to compare Microsoft's results against manually produced human translations.

With other tasks, such as speech recognition, Microsoft says it's reasonably straightforward to tell if a system is working as well as a person because the ideal result will be the exact same for a person and a machine.

Researchers call that a pattern recognition task.

However, with translation, there's more nuance.

Even two fluent human translators might translate the exact same sentence slightly differently, and neither would be wrong. That's because there's more than one way to saying the same thing correctly.

“Machine translation is much more complex than a pure pattern recognition task,” Zhou adds.

“People can use different words to express the exact same thing, but you cannot necessarily say which one is better.

The researchers say that complexity is what makes machine translation such a challenging problem, but also such a rewarding one.

Liu says no one knows whether machine translation systems will ever get good enough to translate any text in any language pair with the accuracy and lyricism of a human translator.

But, he says these recent breakthroughs allow the teams to move on to the next big steps toward that goal and other big AI achievements, such as reaching human parity in speech-to-speech translation.

“What we can predict is that definitely, we will do better and better,” Liu adds.

These recent breakthroughs build on Microsoft's previous work in language translation, including in New Zealand.

Dr. Te Taka Keegan, a senior lecturer in the Computer Science Department at The University of Waikato, is known for weaving together his love for te reo Māori and his love for computers.

In 2005, Keegan worked with Microsoft to translate the company's Office 2003 and Windows XP in Māori.

Today, Keegan continues to consult for Microsoft around ambitious AI, The Translation Hub, which Microsoft hopes will one day offer real-time translations of te reo to English, and vice versa.

Keegan's work of interweaving te reo Māori into technology was recognised by the government last year. Presented to Keegan by Prime Minister at the time Bill English, the Prime Minister's Supreme Award is New Zealand's top teaching excellence honour.

Dr Te Taka Keegan, senior lecturer in the Computer Science Department at The University of Waikato, and former Prime Minister Bill English.

Keegan commented on the award, “Microsoft should share in this celebration and in my award, they really should.

“They were very open to the idea to not only adapt the keyboard but also to translate Office and Windows into Māori. Because of the work we did together, all schools in New Zealand can now offer computing facilities in te reo Māori to children.

“That's an awesome thing.'